Circular Economy; How to Talk about Gaza; My Little Free Libraries

"...We need our poets and our dreamers, the untamed fools..."

Great news: The future economy we want is already arriving. But don’t look for it in Silicon Valley.

Try instead western North Carolina, where The Industrial Commons (TIC) has become perhaps the closest thing we’ve got in this country to Spain’s famous Mondragon network of worker-owned businesses.

Drawing on the area’s long legacy of textile manufacturing, TIC’s mission is “to rebuild a diverse working class based on locally rooted wealth”. (You might want to read that last sentence again, just to let the idea sink in.)

And now they’re building a 40,000 sq. ft. Innovation Campus and business accelerator for the region. TIC’s new 27-acre campus will be a hub for an emerging textile circular economy, a field in which it is already a leader with its Material Return business. The $45 million project recently won a $10M ARISE grant from the Appalachian Regional commission, in addition to funding from the North Carolina General Assembly, and will break ground in late 2024.

But there’s more. In additional to creating an incubator space for startups scale-ups in the circular economy, TIC is a workforce training center whose 100+ employees include Guatemalan immigrant women from their homebase of Morganton NC.

TIC has also built an innovative supply chain for textile businesses in the region, the Carolina Textile District, a coalition of 25 enterprises. Drawing partly on radical principles from Catholic social thought, its visionary founder and now its co-director, Molly Hemstreet (narrating the video above), has brought the project to this scale since its founding only eight years ago. (I wrote about them for Ownership Matters here.)

Let’s hope TIC’s inspiring model of worker-empowered, sustainable, equitable and inclusive businesses is picked up by other communities across the country.

“There are no dangerous thoughts: thinking itself is dangerous.”

—Hannah Arendt

A few months after the 2016 election, I took a look at my still-unread copy of Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism and decided to plough right through it. Published in 1951, the book turned out to be a fantastic read, in which the author traces the overlapping histories of antisemitism, imperialism, and totalitarianism in a series of brilliant set pieces and capsule biographies. Arendt’s insights helped me understand today’s atmosphere of simmering Trumpism in a way no other author has done. (Arendt’s most important ingredient for creating a totalitarian regime? Mass loneliness.)

That powerful literary encounter led me to Bard College’s Hannah Arendt Center for Politics and Humanities, where I discovered a virtual reading group devoted to reading Arendt’s works together. Led by HAC’s director Roger Berkowitz, it was populated by a wonderfully smart group of older and younger folk, all serious readers, perhaps half Jewish by background and half not. We were often 100 or more participants coming together in a thoughtful, non-academic but focused way.

(For more about Arendt, you might catch the podcast episode Pete Davis and I did in 2020 with the wonderful Samantha Hill, then the associate director of the HAC.)

Especially in these vociferous times, I see the VRG, as it’s called, as an island of sanity. It models a kind of rational discussion that engages all through a good-faith system of participation. When I saw that they were hosting a special conversation on the Israel-Palestine crisis, earlier this week I signed up.

The conversation was led by Susan Oberman, an experienced negotiator and the director of the HAC’s Dialogue Project. The group comprised about 40 participants, all of whom had received materials explaining the ground rules. These documents included descriptions of “leaderless dialogue groups”:

Dialogue groups supplement the VRG by providing a space where everyone is given an opportunity to speak and be heard. The dialogue groups are considered public space—confidentiality is not applicable. Speaking and being heard align with Arendt’s notion of appearance in public as an exercise of the most human right, and despite the small numbers, can be seen as an experience in plurality.

After a short introduction from Oberman, we broke into small group sessions for about 40 minutes with the assignment of discussing a recent and somber article on the conflict in Gaza by Judith Butler, “The Compass of Mourning.”

My group of eight individuals, most of whom were Jewish, somehow happened to include three people from the U.K., all of whom expressed dismay at the condition of discourse around Gaza there: “No discussion, no thought,” was their refrain. “Just a lot of nastiness,” one young woman reported.

Another participant pointed out the chilling similarity between Hamas and Netanyahu: “They have both agreed to hate, to feed off each other’s hate.”

One woman protested about hearing the notion that the conflict is a “communication problem”—it’s not something solvable with mediation, she stated pointedly.

“Right now in Gaza a child is killed every seven minutes,” another participant observed with obvious dismay. This despairing comment was countered by a peace activist in the group who pointed out that numerous organizations are hard at work on this terrible situation. She cited Standing Together, Women Wage Peace, the New Israel Foundation, and Peace Now, among others.

Since no solutions seemed possible, no one had much of anything to suggest or even hope for. Which led one participant to note that Butler’s final statement was a plea for help in opening up our narrow social imaginations:

This hope [of eventual peace] no doubt seems naive, even impossible, to many. Nevertheless, some of us must rather wildly hold to it, refusing to believe that the structures that now exist will exist for ever. For this, we need our poets and our dreamers, the untamed fools, the kind who know how to organize.

I’m occasionally asked, Do you own lots of books? I like to reply, not really, I’m down to a few thousand. (More like 800-900, in actuality.)

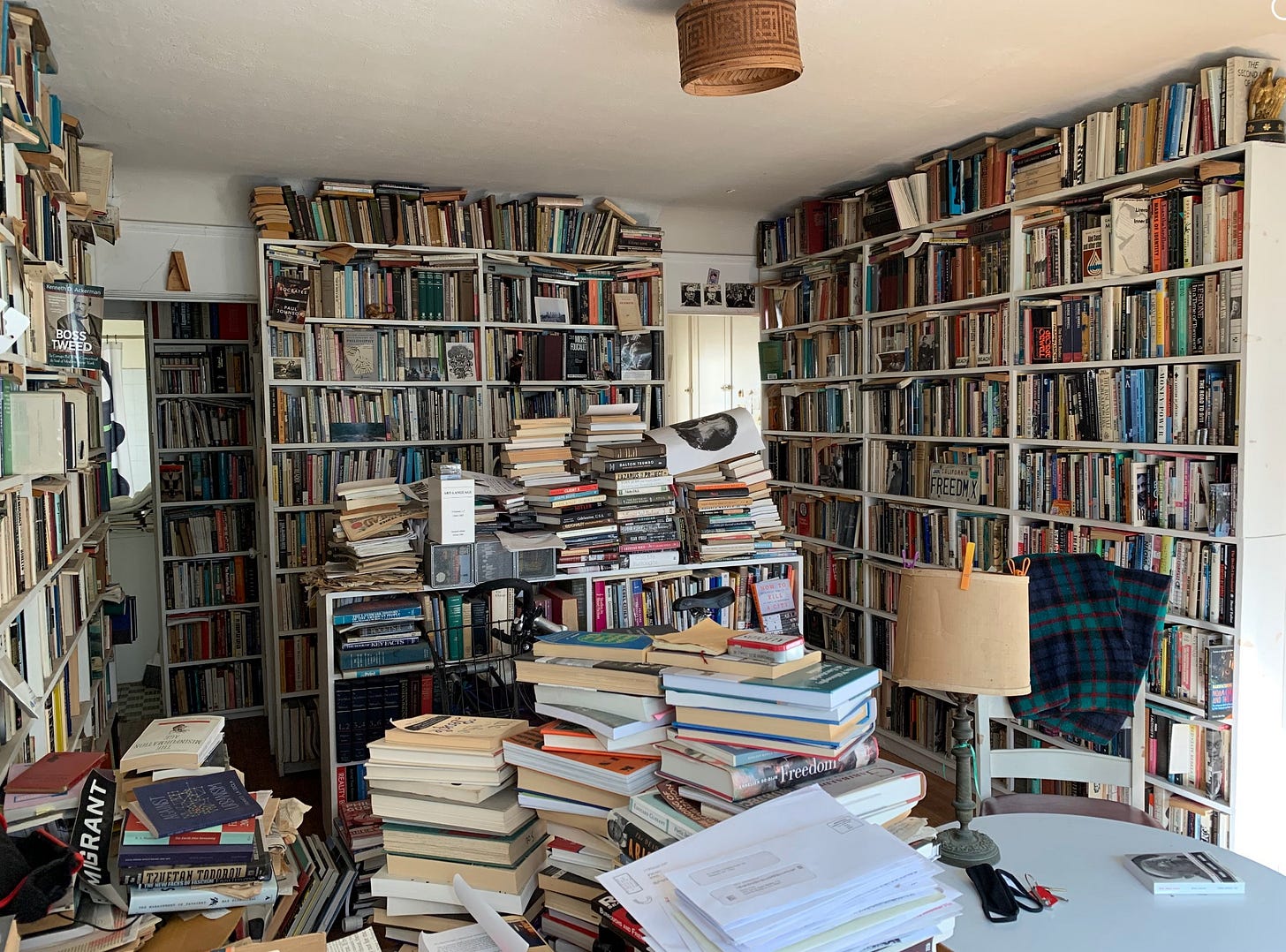

I also console myself that my habit has not taken me to the point of accumulating something close to the small college-sized collection stuffed into a one-bedroom apartment which my friend the late Fred Dewey managed to pull off:

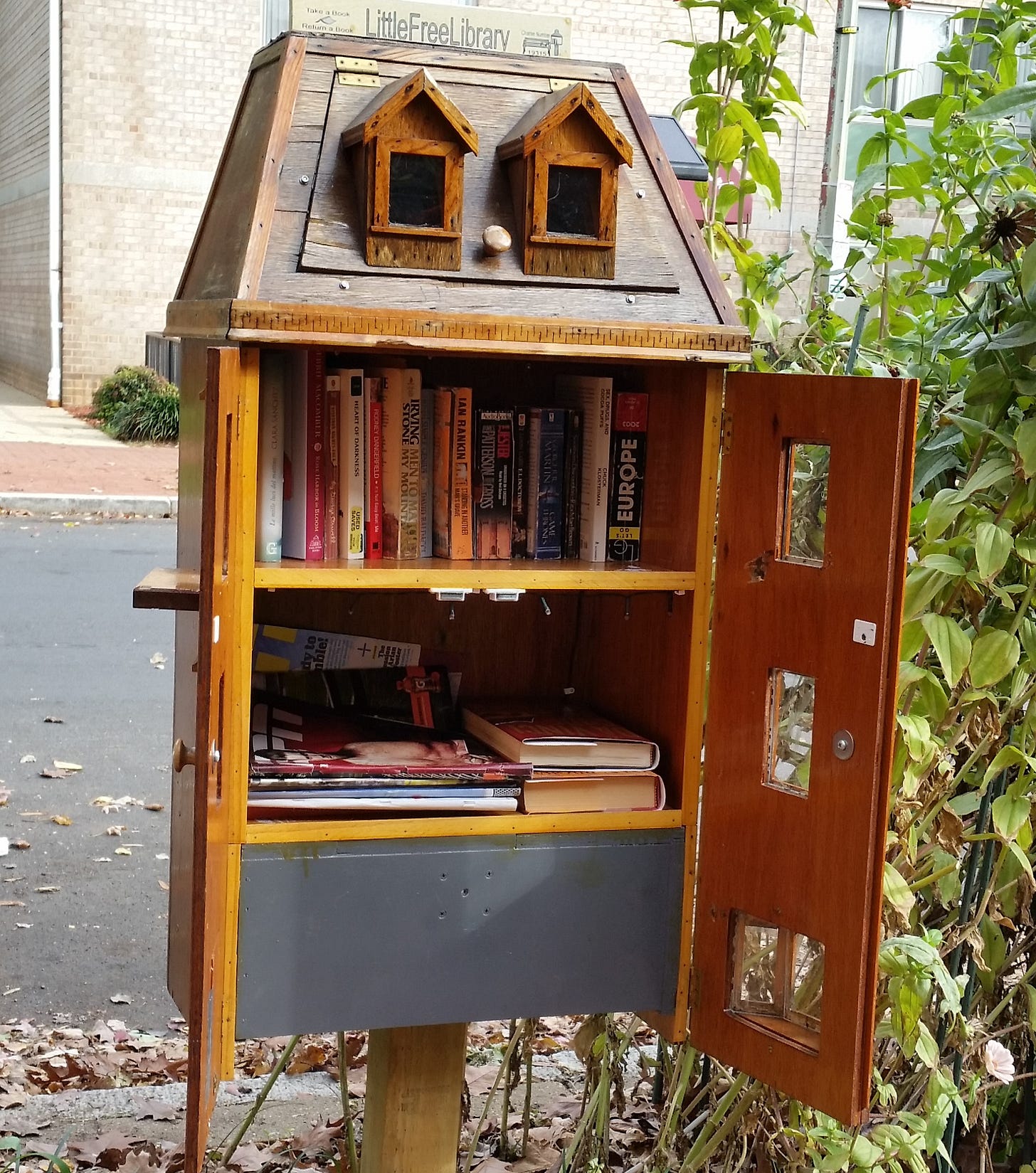

Nor, until my relocation to Washington DC about a year ago, have I ever lived in a neighborhood with Little Free Libraries, much less one with a dozen or so of them, and all within a short walking distance. This is like having a dozen chocolate stores, all of whom leave their doors open for anyone wanting free samples.

Even worse for me, several of the little libraries are kept supplied by very literate folk who unaccountably decide to get rid of their copies of books like Joseph Mitchell’s Up in the Old Hotel, James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, Gandhi’s Autobiography, Ryszard Kapuscinski’s Shadow of the Sun, William Kennedy’s Ironweed, Jill Lepore’s The Story of America, and Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time (Volume 1). I managed to pick up all of these in the last month or so, all in good shape, while just rambling around the area.

To be perfectly snobbish about it, I gotta say some of our little librarians have pitifully little idea of the public taste around here. Stopping in front of certain addresses, I always wince as I swing open the little door, knowing I will come upon stuff like Welcome to Your Face Lift, Muskrat Farming, or Stray Shopping Carts of Eastern North America. More like “free little recyclables” you got there, pal.

See you next time—peace.