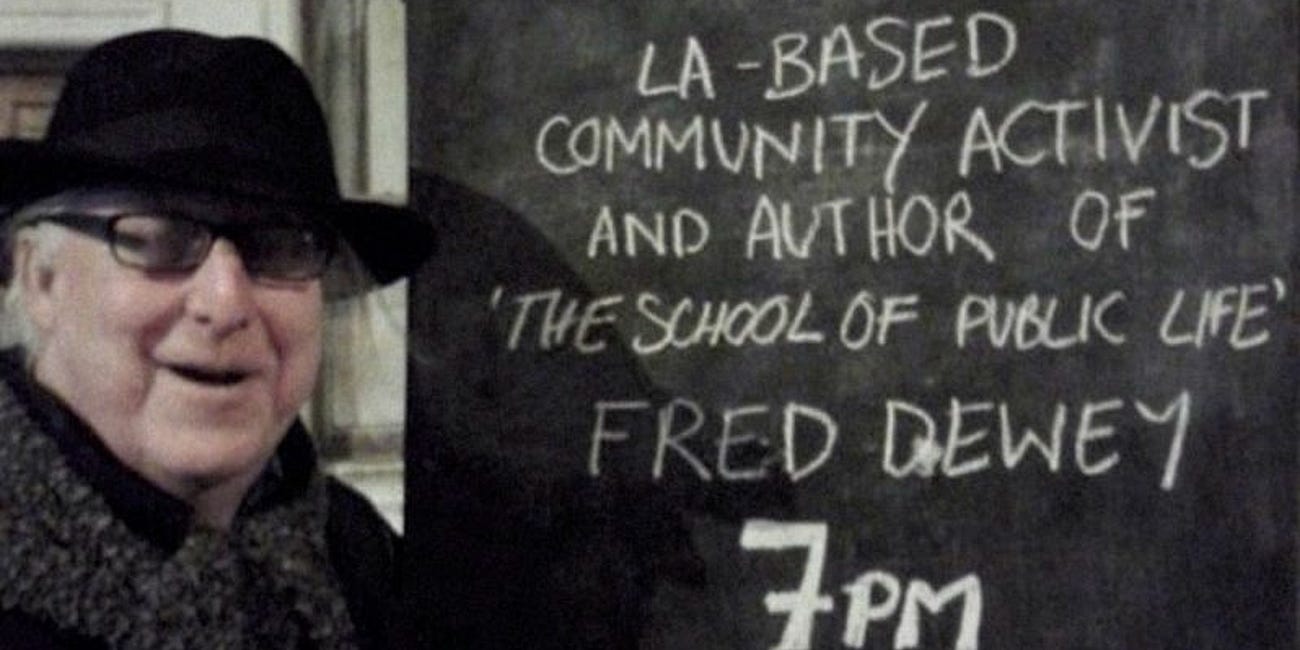

Conversations with Fred Dewey (Part 3 of 3)

Our 2020 podcast with Fred in which he asks, What if we, the people, had rich lives?

Here’s the audio of our conversation with Fred, followed by the transcript below:

Episode #21: Fred Dewey on Recovering Public Life

Pete's back and he joins Elias in interviewing Fred Dewey, author of The School of Public Life and a political/cultural activist. In the aftermath of the Rodney King riots, Fred helped lead a decade-long effort to establish neighborhood councils, now about one hundred, for the City of Los Angeles. Until 2010, he was director of Beyond Baroque, a poetry …

Fred Dewey on Recovering Public Life

A podcast interview with Dorothy’s Place (July 29, 2020)

Elias:

Welcome to the podcast, Fred. We just had a delightful group webinar with you recently but somehow we didn’t spend much time on your wonderful book, The School of Public Life. So that’s what we want to do in this conversation. Fred, how would you like to begin?

Fred:

I’d like to explain why I got so little sleep last night.

Elias:

OK, sure…

Fred:

Which means I am going to start out with something controversial.

One of the things I don't like about activists is–don't gasp, please–is that they’re monomaniacal. And one of the things that I cherish is my enjoyment of culture and all the things that that brings.

So I broke my online streaming virginity last night to join Mubi, which is a wonderful art film site. And I spent more time than I wish to say watching foreign films, one of them being the extraordinary work of the Belgian director Chantal Akerman.

I was thinking about one of your guiding spirits here at Solidarity Hall, Wendell Berry, who talks about what he's learned from farming and everything connected to it. We know that the word culture is one Hannah Arendt talks about and it comes from the word agriculture.

For a single guy like me, culture is like having a family. And it's something I tend to, it's something I cultivate. It feeds me, it nourishes me. It allows me to talk to other people in the community, it’s incredibly valuable.

I mean, there's times when I'm in political meetings when I'm like, “can we just stop and read a poem or something here?” I'm kidding. But because political meetings can be very serious, I'm also not kidding. Because culture is, as you know from having read my book, a crucial part of my life. And it's a crucial part of this thing I talk about in the pamphlet that was really the start of the book, “Polis for New Conditions.” Because this face to face interaction with others is crucial.

In my time as director of Beyond Baroque in Venice CA, I learned something really fundamental about the importance of orality, which is really a fancy word for people talking. I experienced so much live poetry, curating the center. I mean, you know, a couple of thousand readings we did.

When I joined Beyond Baroque, I wanted to run a public space and had written about that for the local alternative weekly, may it rest in peace. They cut out all the political stuff from it. And one of the things about art is that public space is a political thing.

The metaphor for this idea is a table, which is a real world object that you sit around that relates and also separates us. And it's got to be in the world. There's endless lip service to the word public space, but very little real respect for the way in which public space is the space for the life of the people.

So what's the life of the people? Just buying hotdogs and veggie burgers in a public square? It's wonderful to come together that way but for Hannah Arendt that would be called a social gathering. Public space to me is where people come together to govern their condition, period.

Poetry is concerned with meaning, as is politics and culture. These things are woven together. When you’re an activist, it's so funny, the way I've struggled when people ask me for a short bio. How do I describe myself? I would love to take the term you used in the workshop, Pete, super citizen–it was very flattering.

I'm not super although my avatar that I created for the book, Freedom X, was kind of like a super citizen. I vividly remember jumping off the couch in the living room when I was eight years old, wearing my little Superman outfit. And recently I created this avatar, called Freedom X. That was a cultural move in the book. And it was a cultural move in my life because I used it as the title of a column I wrote.

Anyway I took on Beyond Baroque because it was a public space. And this was after I started the neighborhood council work in Los Angeles–they were completely separate tracks. Most of the Neighborhood Council people have probably never even read a poem and they probably don't go to movies like I do. I mean, I love movies, I was up until way too late last night watching them. I've even worked on movies.

And I just think that the point of this is that politics is about all of us. It's about ordinary people. It's about people who are living their lives, who are really stressed for time. They've got this thing and that going on.

And these are all things they can bring to bear they should bring to bear in politics, coming together with others and trying to figure out how do we have better conditions? How do we govern our conditions, because there's so many processes geared to steering us away from doing that. It's like, politics is what we see on TV, politics is what we see at political conventions, in political parties, in the White House.

Well, where's our politics? Where's the politics for the people? Where's the public life of the people? And that's why the book starts out with “What about the people? And we don't realize the stakes here in this confusion.

So I wanted to take on a cultural center where I could bring people together, people who were interested in poetry, but I also brought in Robert Fisk, the wonderful international journalist, as well as amazing poets from Asia, North Africa, South America, Central America. And more importantly, people from around Los Angeles.

I realized last night thinking about this interview, that I actually have some weird need to dig down to the roots of things. There's a wonderful Swedish philosopher Sven Lindqvist who wrote a book called “Dig Where You Stand”--it’s the foundation of a whole historiographical movement.

The Importance of Place

Pete:

Yes, it’s wonderful, I just learned about it last month. It's unbelievable, tens of thousands of participants. Tell me if I'm getting this right, Fred. Lindqvist basically argued that you should research the deep history of the area immediately around you. So if you're working in a factory, you should look into the strikes that happened 40 years ago in that factory.

Fred:

Exactly. I find it fascinating because Lindqvist put it so simply in his manifesto. And yet his idea is extremely threatening, because our whole system is geared to keeping us from standing where we're standing and knowing what's underneath where we're standing.

And this is why Wendell Berry or Christopher Lasch or some of the other guiding spirits you cite at Solidarity Hall are so important. Because if you can't learn about and take responsibility for where you are, and then commit yourself to that–and that's the hard part, committing yourself to it–you're screwed.

OK, I've wandered over about six different topics, but what led me to mention Lindqvist was one of the key aspects of running Beyond Baroque–which was learning about the town of Venice. And learning about the Venice poets and learning the history of that building and learning about the history of the community, bringing in those historic literary figures, having them read with us, publishing them, bringing in the local neighborhood council into our theater space.

I knew that these things were stitched together, and that culture is so important for understanding history. If you can give people a way to recover what they've been robbed of–I know that's a bit harsh, but I really feel that. I end the introduction to my book by saying, I found myself in the middle of an undeclared war.

I really felt like being grounded in the neighborhood was almost impossible. If you wanted a pothole fixed, fine. If you were okay with the community watch group, fine. If you're okay with the various bosses running the neighborhood, fine.

But a real neighborhood is more than that. And a neighborhood has history. And to understand that history, you sometimes need poetry, or you need film, and you need gatherings most of all. But our society, our world is so barren of these things.

A Different Take on U.S. History

Elias:

Fred, I want to go back to the book and your wonderful historical analysis of how we got to this place. From the New England town meetings down to today’s two party cartel. Could you give us here a brief overview of that historical theory that you unwind so wonderfully in the book. It’s a big story, I know.

Fred:

And yet it shouldn't be a big story.

The beginning is the Mayflower Compact, when people came together and made a compact to govern their conditions. It was all the males on the boat, so obviously there were a bunch of people who were not at that compact. They got to New England where they learned from the natives, watching how the natives governed the land, and tended for it and cared for it. So anyway, New England birthed this new form, and it was completely new. John Locke, the great apostle of the social contract theory, actually wrote his stuff after learning about this neighborhood form of government in the colonies, New Englanders coming together to meet once a week, once a month, discussing what's happening in the town, face to face. Farmer John is grabbing the land of farmer Tom, and they have to negotiate all this and make laws in the town meeting, since there were no laws.

So people were held to account if somebody was screwing somebody else. Economically, they had to deal with it. Okay, so this started in the mid-17th century with Plymouth settlement which you could describe–thinking of Jamestown’s plantations and slave trade–as the anti-plantation.

The people on the Mayflower started this practice of town meetings, and then they spread. There were clashes, but there was a lot of comity. And it was troublemakers who started the clashes with the Native Americans, with whom there had been a lot of communication back and forth.

Interestingly, the British were not so happy with these town meetings, because they tended to make people very independent. They realize they don't need an overarching government sitting on top of them telling them what to do. So the farmers, mainly farmers, they were very ornery and this became a problem. And Boston was the place where the clashes began, that we all know so well. So. So the British tried to impose their empire on New England and failed.

At this point, the New Englanders began to abolish slavery–there was some slavery in New England which is also seldom told. So these people decided they needed a larger form of government as the town meetings spread. There were other settlements–mainly in the South–that were not based on a town meeting. And that became a big problem.

But the New Englanders formed a government. We know about the Declaration of Independence and then the Constitution with its Bill of Rights. Meanwhile there was the problem of the south where there was no town meeting form of government but there was a little problem called slavery. And the Constitution said a black person was only three fifths of a person so this is really a grievous problem, the racial inequity of it. It has big future implications.

And this is just not discussed. I mean, we hear about reparations. Okay, I understand that, let's get together and figure it out. But the problem with being three-fifths of a person is that you're not a person, first of all, and the two fifths that's missing is the important part, which is governance, intellect, opinion, experience. The other three fifths are labor, and unpaid labor on top of that, so it's just it's it's abominable, chattel slavery, it is the most disgusting form of social and political organization on Earth.

And the Americans perfected it. And not only did they perfect it, they modernized it, another thing you don't hear about. So the Confederacy which formed out of this slave power, this enormous, built-up wealth that tremendously benefited New York City and New Haven where the insurance companies were. The South said we believe in the Declaration of Independence, we believe in freedom, we believe in rights for some of us.

And the debates between Lincoln and Douglas are amazing on this subject, because Lincoln is so sharp. He's like, well, Mr. Douglas, you believe in freedom, but you don't believe in freedom for everybody? What is your freedom worth? It's full of stuff like that, Lincoln was brilliant which is why he went so far.

So the Confederacy, which had erected itself on this heinous principle, was defeated and a lot of people died. It was a very bloody war and that should tell you something about how strongly the New Englanders especially fought. Because for them, it was heinous, an outrage.

And it wasn't just Lincoln, it was Frederick Douglas and all these others, right up to Malcolm X, who has this wonderful quote, something to the effect of “nothing has damaged white people more than having these shuffling ‘yes, massa’ people”--it has destroyed the white people of the United States. Very interesting thought. And Lincoln made observations like this.

So New Englanders hated this system. There was a wonderful film some years ago called Gettysburg. Everybody should see it–I think I saw it five times. And Joshua Chamberlain from Maine leads the battle. And what was the battle about? The meaning of freedom, this terrible, degraded word that is so misused and propagandized.

The problem here is we need to reclaim the words we need in order to govern ourselves, we need that word freedom, we need to take it back. Just like we need to take back citizenship and naturalization and various other words.

So the Civil War was a battle over principles. And over the meaning of principles. What do these principles mean? What does the Declaration mean? Lincoln, with a lot of help and sometimes even pressure from many decent, honorable people who cared about human beings and many very amazing Black folks, they somehow managed to pull this thing out of the fire and put the union back together. And then they launched Reconstruction, one of the great liberation movements in human history that is never described as such.

Eric Foner has done some great work on Reconstruction, following in the footsteps of his amazing historian father, Philip Foner. So we have buy-in for “a government of, by, and for the people”, thanks to Lincoln. That is about as simple as you can possibly get. It's a great axiom. I try to say it to myself every morning. So the principles won, to a great extent, but Lincoln was killed.

And he was replaced with a cracker Southerner Andrew Johnson, who then proceeded to fight reconstruction at every step. A lot of Republicans, people like Thaddeus Stevens, still fought back, so Blacks in the South got some independence, but then it was undone and reversed.

And most important in this reversal, I believe, was the Supreme Court’s adoption in 1886 of a reading of a case called Santa Clara County v. Southern California Pacific Railroad. Everyone's probably heard something about the idea of corporate personhood. This is where it started. But the discussion today does not really delve into what the meaning of this horrendous maneuver was.

Southern Pacific Railroad was one of the first real cartels, which means it was a monopoly, it was controlling the railroads. So one of the counties out west sued them. I've never actually read the entire decision because the decision is not what's important. What's important is what the Supreme Court Clerk did. And I just wonder what family fortune came out of that bag of cash. The clerk inserted into the description of the meeting a phrase indicating that the consensus of the meeting was that corporations are persons. It was not a legal decision. It was inserted by the clerk in collaboration with the Chief Justice whose name I refuse to mention.

Pete (laughing): You're probably the only person in America who refuses to mention his name…

Fred:

Yes, I refuse…

Pete:

Should we mention him for you? It was Judge Morrison Waite, the infamous Waite.

Fred (laughing):

Ugh, my ears are bleeding.

Elias:

May he live in infamy.

Fred:

Well, his legacy lives on with us. I'm becoming more and more militant on this–it basically destroyed the country for the future. Now, there's been huge resistance to the principles embedded in this one-sentence maneuver.

This is politics, folks, this is how it works. Somebody inserts a sentence in the Supreme Court decision. And then the next 150 years, you're trying to get it out. So there is not just one original stain on this country. There are several stains. And this is a big one.

And why is it a big one? Because I believe one of the parties, most likely the Democrats, were behind this and also because–and here’s something that few people know–our parties are corporations.

So what they snuck in was the idea that a conglomeration of people, in private out of the public’s sight, out of public reach, have the rights of the Bill of Rights. Which means the freedom of assembly, freedom of speech. You can't abolish them, you can't criticize them, you can't stop them, you are simply F **** D!

The consequence of this was a kind of cartel political structure for the United States, and the subsequent court decisions confirmed this non-decision as a precedent.

When Corporations Were Radical

One thing to remember is that corporations in the United States originally were radical in nature. This is something else we don't hear much about today. A corporation was the people coming together, in a New England town, saying hey, we need a bridge, we're all getting stuck in the stream. So the people come together, and they form a public entity which can then be dissolved by the people in the next town meeting, once the bridge is built.

This is what was changed in 1886, this principle of public life, and it became a secret. And this is the worst part of it, this abomination. And what I argue in the book–which I don't think anyone else has ever argued–it was kind of a deduction.

When you put 30 people together, and you give that group the rights of one person, who's gonna win in a debate? It's like saying, okay, the 30 people over there have as many rights as I do. But there's 30 people there. So it's absurd, because I should have as much right as the 30 people. In other words, I, as a citizen, should have as much right to abolish Exxon as the 300,000 people at Exxon–not me personally, but we individually coming together, we have the right to govern our conditions. And that means to establish and to abolish, not just watch TV.

So this is my theory, my intuition–this extended and revived the three-fifths principle. It made everyone in the United States a slave. And from there, I mean, it took a really long time because the people revolted, they arose. There were fantastic, multiracial movements. You know, I mean, there were so many great people, the stream and tradition of liberty and freedom in this country is still powerful and strong.

But that little decision is standing there in the way. It's what's blocking the people's power, because the people will never, ever be able to have as much power as secret and private agglomerations of other people that have rights to not be dissolved, to not be attacked or critiqued. And this is what the two parties rest on

Elias:

This is what you call in the book “the cartel”.

Fred:

Yes. People might be familiar with the term monopoly. But actually the term cartel is more precise, because it's something set up by the government. Yeah. And for a contemporary example, where did Bill Gates get his deal? He got it through DARPA, the Defense Department program. And his mom was working for the Democratic Party. So Bill got some very special favors, shall we say.

Microsoft for a long time was a cartel. These are no longer corporations formed by the people in assembly to address public needs. The entire structure of the society is upside down, like science should be dedicated to informing the people about what's available, what's possible, then the people make their decision. They say we want our rights preserved, you know, all the things that people do when they come together. And then we build our technology, we build that bridge across the stream. And if it washes out, we rebuild it. We reform the corporation, but once the bridge is built, we dissolve the corporation. I can tell Pete is on the edge of his seat with a question…

Pete:

Yes, just to respond to that, I totally agree. I worked with Ralph Nader for many years. So I've drunk the true Kool Aid, or I guess it's the water of truth, on this. Which is that corporate supremacy is strangling our democracy. If I had to push back a bit, I do wonder if we risk misguiding people if we say that there was this moment of a flipped switch in 1886. And if we got that fixed, or if we repealed Citizens United, or if we say everything went wrong with the Powell memo…

But I do think the lesson we need to teach people is that there needs to be a civic wave that displaces the corporate wave. I kind of buy Eugene McCarraher’s argument that corporate capitalism is a counter religion, a counter politics. We don't appreciate it enough, how it’s seen by its practitioners as a set of things that give you meaning, a set of default options, almost a religion unto itself. And the only way you can fight an idea is with an idea.

Fred:

Yes, and you're absolutely right to bring this up. These corporations are not truly public. And we need public control of the corporations. There was a weak effort in that direction with things called public utilities. But the point here is the life of the people and this wonderful term called free enterprise. Anybody who runs a small business knows who controls the levers. It's not the small businesses. It's not the enterprising Americans and it's the enterprising Americans that built this country. They built it.

So the corporations are enemies of free enterprise as far as I'm concerned. And an assembly of people to govern conditions is a free enterprise. We don't need to have a history seminar here but we have to understand the gravity of this situation. And that's why I make the link to slavery.

Because we are in effect in that horrible condition. It's very interesting that the word capital etymologically comes from the word chattel.

What if you were to begin to think about the possibility that capital is actually not the friend of free enterprise, in the way that it's accumulated and concentrated? And that actually, wealth is what we all build together when we need to get something done?

Imagine if we had an internet as the original scientists envisioned it–as a community-built enterprise? It would be totally different from what we have, a lot more wonderful, and with a lot fewer sinister elements.

So the point of this argument is not to make people feel powerless. It’s to make them realize they have the power. And this is what we were talking about in the workshop a few weeks ago. It's the people that make these systems function and work. So why can't we govern the systems? That's all I would ask.

Pete:

I have a favorite Lincoln quote about this. At the Wisconsin State Fair, before he was in the election. Before he was president, he was at the Wisconsin State Fair. Among many things you hit the nail on the head with is that this kind of radical Lincoln is not appreciated. You read his full speeches, and it's all about this idea of free labor. And that free labor is against slave labor, but it's also against wage labor.

About this time Karl Marx used to write him letters about this, which I think people don't appreciate. I'd love to send the current Lincoln Project, which is made up of a bunch of Never Trump Republicans, some of Marx and Lincoln's correspondence.

I think Marx was writing for the New York Herald at the time. And Lincoln at the fair is talking about how they’re learning all these things about how to own their own land. And about how we need to all come together and teach each other and then you're gonna use these skills to have your own piece. And when you have your own piece of land, and we're all together in this, we are protected from–and here's the quote–”crowned kings, money kings and land kings”.

The crowned kings are the British Crown during the American Revolution and today’s government, the money kings are the New York financiers that tried to control things, and the land kings are the Southern plantation class.

Fred:

But also what happens right after Lincoln is killed is the ranchers out west who Teddy Roosevelt went out and fought for, the small ranchers, who were fighting the big ranches. So that land problem carries on from the plantation south.

Pete:

Fred, can I ask one more question? One of the things I love that is so apparent as you talk is that you're from this tradition of civic and radical democracy that I can only explain through this one metaphor from the open source community. It’s called the cathedral versus the bazaar. How I basically interpreted it is there's one way to think of politics, which is there is some perfect utopian cathedral out there. We need the perfect expert engineers to build the perfect thing alone. And the dream is we're all just scientists trying to discern some perfect cathedral.

And the only problem with our situation today is how distant we are from the perfect cathedral. And I think that's totally wrong.

Democracy is about the bazaar: it's about all of these people in all these shops and meeting in between them. They can be taken down and put up anywhere, full of life. And there's no way of saying what the perfect bazaar is. It's only measured by how lively it is. That's the democracy I love. And I think you are from that tradition. Am I wrong about that?

Fred:

No, you're right. And very well put, Pete, especially the Lincoln quote. Yes, that's really prescient, it tells you something about a freedom tradition in this country. James Baldwin has a wonderful quote about how “we need to squeeze water from the rock of inheritance”. An incredible quote, which tells us that our inheritance is a rock and how do you squeeze raw water from a rock? He of course was talking about slavery, but also many other things.

What Makes Us Secure?

Elias:

One last question and then we we're almost out of time. On the other side of what Pete was describing–this wonderful, local communal feeling we get in the neighborhood assembly–there are people listening who might say the idea of government at that scale handling public safety makes them uneasy. It might be risky. And in the book, you make a very specific comment, which was slightly startling to me and really got me thinking. The comment was “self government is our only security.”

Fred:

Right, that's the fundamental first principle.

Elias:

You mean, we don't actually need the military industrial complex?

Fred:

Who won the American revolution against the greatest empire on the planet? It was farmers, farmer Joe and farmer Tom and their suffering wives. I mean, absolutely, self government is our only–and I emphasize the word only–security.

And it's because it fosters enterprise, as Pete was talking about, and innovation, and solidarity. And it is unbeatable. It's the great principle. Locke did his version of it and Martin Luther King did his version of it. And Malcolm X.

One of my teachers said, look, this system is just unreformable. But you know how you could reform it? You let Black people have their own self-governing structures, and that will percolate throughout the entire system. And we'll change the system in the direction we want it to go.

And there's a great truth in that, because the people who have the least power are the first people who should have self government. We're learning so much from the Black community, they're teaching the whole country and the whole world. Because they understand the freedom principles. So self government is our only security.

My teacher, Harvey Shapiro, taught me this term first principles. And I think people on the left need to reclaim this because there's actually just one principle–the one you just stated. I am so appreciative that you mentioned it because it is the basis of my historical analysis.

But importantly it's also what steered me through the neighborhood council fight in L.A. Because I realized even when the system was trying mightily to thwart us through all kinds of gimmicks and magic shows and smoke and mirrors, and it was ferocious, the only thing that kept my head screwed on was this: that there's no security unless you govern your own conditions. It starts there. Everything starts there.

Elias:

And the practice of self government, as the title of your book suggests, is itself a school?

Fred:

That's the most important part of it. Because you learn about what it means to govern your own condition. It's tough. In the webinar you held with me, somebody asked, “Fred, you said power is easy. It's the easiest thing. But if power is the easiest thing, why is politics so hard?”

It's hard because we don't have what Hannah Arendt called the space of appearance, we don't have the space to come together, to find out our condition, and then to do something about it.

And that's why self government is the only security. If you can't talk to somebody else who is suffering, how are you going to answer them, because you don't realize there's other people suffering the same way you are. We're all suffering under these conditions. And if you can't talk to other people and find out they're having the same problem, then you'll never get together to fix it.

And so this goes directly to addressing the problem, as I talked about in the book–the subject of remedy and repair. Repair is the big thing that we really, really need. When I speak of revolution in the book, I am talking about something peaceful. I'm not talking about heads on pikes.

In L.A., all we did was change the law in the city. Now that was hard. But it actually wasn't that hard at all because the system is so blind. It doesn't know what's going on. It manufactures one reality after another, which gets into the subject of the next book, which is propaganda, that it really doesn't know what it's doing.

And Arendt did a wonderful book about Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann, who couldn't think. Why couldn't he think? Because he was a career climber, because he grew up in a culture that had no self government of the people at all, no accountability. He could invent these massive schemes that were just absolutely horrific without any recognition of what was going on. He couldn't, as Hannah Arendt put it, stand in the shoes of other people.

And I like to think of the town meeting principle versus, let's say, a kind of proto totalitarianism–the clash of these two principles is what we're facing right now. Can the people come together?

First of all, they have to have the space to do it. Most don't, some do. It's still very strong in parts of the country. But this practice of understanding that self government is our only security versus all these other claims, like “technology will solve our lives”, “the market will solve our lives”. No, no, no.

Take eight people in a block coming together and saying, wow, things are not going so well. What are we going to do about it? And that's where they meet the wall, the bulldozer. That's where they meet the local city council that couldn't give two you know whats about them.

So the problem is: how do the people reclaim that understanding that their self government–together with others–is the only security. There is no other security.

Elias:

What you’re saying reminds me that one difficulty with some neighborhood assemblies is the lack of neighborliness shown in their fear of their own neighbors. It’s a great obstacle to building anything if we have this propagandistic notion that we can't trust each other. So is your new book going to be touching on that?

Fred:

Well, that's really interesting. You've just planted a thought in my head, which I hadn’t really put together. Because one of the texts I wanted to use as a piece I wrote on a really scandalous term–the “n” word plus “ology”--coined by George Wallace in 1968. He was losing the election because his opponent was being a bigger racist than him–and Wallace was not originally a racist.

But this ugly term came out of Confederacy days. And the idea was: when out campaigning, you don't just holler the N word, you promise the moon first. In other words, you say, I'm going to give you everything–like we heard in the Trump campaign. I'm going to give everybody jobs, I'm going to get out of the wars, I'm going to protect your healthcare. I'm promising you the moon.

But then you add, “these bad guys are after us”--and that's what he used to break all of his promises. And Hannah Arendt says promises are the only thing that keep the society and the body politic together. So he broke all his promises.

When you promise the moon and holler the N word, you divide people. That's why I talked in your webinar about these poetry programs in which we brought together the neighborhood, getting people in L.A. to cross town and talk to each other and not to be afraid of each other.

One of the participants in the webinar said, What about somebody sitting next to me who is totally opposed to what I want? Well, hello, that's politics. But you can't just stop there: you got to say, we're all in the same boat. We're all together in this world. So let's work this out because we want to protect the world we want.

Everybody wants to protect their community. This is why I love the idea of neighborhood councils. Because everyone wants to protect the neighborhood. But here we come back to that originary principle, self government is the only security. Everyone–including the people ranting and raving at each other–they also believe this. They just have a different idea of what self government is and what security is. But it's the same principle.

And so your question is really good, how do you deal with this fear? How do you deal with the hatred that is stirred up by politicians, daily hatred, and 400 years of grievances? How do you deal with this? That's a great question.

What If We Had Rich Lives?

My belief is–and this is was the point of Shapiro's amazing comment about giving Black communities self government–once you do that, once there's a space where people have power to govern their conditions, I really firmly believe things get worked out. And not only that, it ripples outward. It's so powerful.

And I was thinking last night, what if we had rich lives? Like, what if we had rich neighborhoods that were full of the differences that fed each other and inform each other, as per your wonderful quote earlier, Pete.

What if we had a rich world? What if we had a world where all the knowledge formation wasn't locked away in the ivory tower? What if we had a rich world where enterprise was rewarded and protected? What if we had a rich world where people were educated? These are all things you need for self government and if you demand self government, you also demand the resources to do it. Those resources include comity, friendship, understanding, knowledge…

Elias:

Fred, that’s great, I think that's a final vision for this conversation.

Fred:

No, no, that's just the beginning!

Pete:

Democracy is never final!

Fred:

That’s right, thank God!

Pete:

The bazaar continues!

Elias:

Thank you friends, we will ride again.

See you next time—peace.